Matriochka

[Nuit du Hack Qualifiers, 2016]

- Category: Crack Me

- Points: 50, 100, 300, 500

- Description:

Can you help me?

Recently, I found an executable binary.

As I'm a true newbie,

Certainly, to solve it, I will have difficulties.

Keep in mind, the first step is quite easy.

Maybe the last one will be quite tricky.

Emulating it could be a good idea.

The challenge is available at : http://static.quals.nuitduhack.com/stage1.bin

Write-up

So we started of with a binary and a vague description. We could see that there are 4 challenges in the scoreboard, which are all called Matriochka. We are not given a binary for the stages 3-4. As it turns out, each of the stages printed the next stage, when given the right password as command line argument.

Stage 1

This one was pretty easy: strings. My colleagues already solved this one when I started playing.

[0x00400560]> iz

[...]

vaddr=0x0040e062 paddr=0x0000e062 ordinal=4719 sz=23 len=22 section=.rodata type=ascii string=2$^HxUsage: %s <pass>\n

vaddr=0x0040e079 paddr=0x0000e079 ordinal=4720 sz=26 len=25 section=.rodata type=ascii string=Much_secure__So_safe__Wow

vaddr=0x0040e093 paddr=0x0000e093 ordinal=4721 sz=12 len=11 section=.rodata type=ascii string=Good good!\n

vaddr=0x0040e09f paddr=0x0000e09f ordinal=4722 sz=14 len=13 section=.rodata type=ascii string=Try again...\n

There were a lot of other weird strings, probably the next stage.

So let's try Much_secure__So_safe__Wow.

./stage1.bin Much_secure__So_safe__Wow 2>./stage1_out.base64

Good good!

On stderr we get some base64 encoded data, which turns out to be the next stage.

$ cat ./stage1_out.base64 | base64 -d | tar x

$ file stage2.bin

stage2.bin: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.24, BuildID[sha1]=7b2fd52d0de50c9e575793a0fd17fdd2574c5c53, stripped

Stage 2

Stage 2 again validates a password. If we look at the Control Flow Graph of the

main function (using radare VV and zooming out)

<@@@@@@>

t f

.------' '------.

| |

| |

[_072d_] [_0708_]

f t v

.-----'.' .--'

| | |

| | |

[_076b_] | |

f t | |

.----'.' | |

| | | |

| | | |

[_0784_] | | |

v | | |

'----. '. | |

| | | |

| | | |

[_078b_] | |

[...]

[_093e_] | | |

v | | |

'----. '. | |

| | | |

| | | |

[_0945_] | |

f t | |

.----'.' | |

| | | |

| | | |

[_0978_] | | |

v | | |

'----. '. | |

| | | |

| | | |

[_097f_] | |

f t | |

.------' '--. '-. |

| | | |

| | | |

[_0985_] [_099a_] |

v v |

'-----------.-----------'

|

|

[_09b3_]

We can see a very clear pattern. If we take a look at the first part

[0x0040076b 5% 230 stage2.bin]> pd $r @ main+121 # 0x40076b

│ 0x0040076b c745ec010000. mov dword [rbp - local_14h], 1

│ 0x00400772 488b45d0 mov rax, qword [rbp - local_30h]

│ 0x00400776 4883c008 add rax, 8

│ 0x0040077a 488b00 mov rax, qword [rax]

│ 0x0040077d 0fb600 movzx eax, byte [rax]

│ 0x00400780 3c50 cmp al, 0x50 ; 'P'

│ ┌─< 0x00400782 7407 je 0x40078b ;[1]

│ │ 0x00400784 c745ec000000. mov dword [rbp - local_14h], 0

│ │ ; JMP XREF from 0x00400782 (main)

│ └─> 0x0040078b 488b45d0 mov rax, qword [rbp - local_30h]

[...]

Basically here the first byte of the passed argument is checked and if it isn't

equal to P then 0 is written to [rbp - local_14h]. At the end of the

program if this is 1, the password is validated.

So I reversed the first three characters of the password, but then it got annoying. There must be a better. Now I always wanted to try angr , a symbolic/concolic execution framework by the shellphish guys. I never used it so I read some examples and quickly whipped up a script to solve this challenge:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import angr

import claripy

def long_to_str(l):

"""We get the bitvector as a python long and we need to convert it"""

x = []

while l != 0:

x.append(chr(l & 0xff))

l = l >> 8

return "".join(x)[::-1]

p = angr.Project("./stage2.bin")

# avoid the BBs that do

# mov dword [rbp - local_14h], 0

avoids = [0x400784,

0x4007a9,

0x4007e0,

0x400826,

0x400855,

0x400884,

0x4008b8,

0x4008e7,

0x400904,

0x40093e,

0x400978,

]

# target the write block

target = 0x00400993

# found through manual reversing

flaglen = 11 * 8 # in bits

# the flag is the only symbolic input

flagsym = claripy.BVS('arg1', flaglen)

# create the memory state of the program

state = p.factory.entry_state(args=['./stage2.bin', flagsym])

path = p.factory.path(state)

# launch the Explorer. angr will try to find a execution path from the

# entrypoint to the target address (the stage3 printing), while avoiding

# the basicblocks that set the found bool to 0.

# This should gather enough constraints on the symbolic flag, that there is

# only one possible input to trigger that path.

ex = p.surveyors.Explorer(find=(target, ), avoid=avoids, start=path)

ex.run()

if len(ex.found) > 0:

#print "Found path:", ex.found[0]

for flag in ex.found[0].state.se.any_n_int(flagsym, flaglen):

print "possible flag:"

print flag

print long_to_str(flag)

else:

print "Nothing found :("

Let's see the output:

$ python solve_stage2_angr.py

possible flag:

97174171495276010235913313

Pandi_panda

$ ./stage2.bin Pandi_panda 2>stage2_out.base64

Good good!

$ cat ./stage2_out.base64 | base64 -d > stage3.bin

done :)

Stage 3

This is a very interesting binary. Instead of using normal calls, the binary uses signal handlers to perform control transfers.

[0x0040114b 23% 230 stage3.bin]> pd $r @ main+90 # 0x40114b

│ 0x0040114b befd074000 mov esi, sub.signal_7fd ; "UH..H.. .}.....8 " @ 0x4007fd

│ 0x00401150 bf0b000000 mov edi, 0xb

│ 0x00401155 e866f5ffff call sym.imp.signal ;[3]

│ 0x0040115a be50104000 mov esi, sub.fwrite_50 ; "UH..H.. .}.H..>0 " @ 0x401050

│ 0x0040115f bf08000000 mov edi, 8

│ 0x00401164 e857f5ffff call sym.imp.signal ;[3]

If we look at the first signal handler, we can see that it registers another signal handler.

[0x00400836 11% 230 stage3.bin]> pd $r @ sub.signal_7fd+57 # 0x400836

│ 0x00400836 817dfce70300. cmp dword [rbp - local_4h], 0x3e7 ; [0x3e7:4]=0

│ ┌─< 0x0040083d 7e09 jle 0x400848 ;[1]

│ │ 0x0040083f 817dfce80300. cmp dword [rbp - local_4h], 0x3e8 ; [0x3e8:4]=0

│ ┌──< 0x00400846 7e02 jle 0x40084a ;[2]

│ ││ ; JMP XREF from 0x0040083d (sub.signal_7fd)

│ ┌─└─> 0x00400848 eb10 jmp 0x40085a ;[3]

│ ││ ; JMP XREF from 0x00400846 (sub.signal_7fd)

│ │└──> 0x0040084a be5c084000 mov esi, sub.signal_85c ; "UH..H.. .}..E." @ 0x40085c

│ │ 0x0040084f bf0b000000 mov edi, 0xb

│ │ 0x00400854 e867feffff call sym.imp.signal ;[4]

In total there are 22 signal handlers, which register the next signal handler on success.

> afl~signal_ | wc -l

21

fcn.0040100e is the last signal handler, which doesn't register another

signal handler. I don't know why radare didn't rename this one. So we can

assume that the password will be 22 bytes long, since every signal handlers

seems to check exactly one byte.

Using angr again is probably gonna take a

little work. Just launching an Explorer like in the previous example results

in some error, that a syscall is not implemented. I assume it's the signaling.

We could somehow patch the binary, or hook the signal calls. After some

brainstorming with a colleague, we thought that there might be some

"side-channel", we can use the bruteforce the flag byte by byte. So I

experimented with strace a little. The first thing I noticed is that there

are always 1023 calls to kill, triggering a segfault. We can confirm this

using radare, that this happens in the main function.

$ strace ./stage3.bin asdf 2>&1 | grep kill | wc -l

1024

We can also get the number of registered signals using strace:

$ strace ./stage3.bin asdf 2>&1 | grep sigaction | wc -l

2

These are the two calls to signal in the main function. If we guess a

character right we should see one more call to signal. So I whipped up a

quick shell three-liner:

$ for x in A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 '{' '}' '!' '@' '#' '$' '%' '^' '&' '*' '(' ')' '-' '-' '_' '+' '=' '[' ']' '.' ';' '\\' '/' ',' '<' '>' '`' '~' "'" '"' '?'; do

echo "= $x ="; strace ./stage3.bin "$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x$x" 2>&1 | grep sigaction | wc -l

done > log; cat log | grep -B 1 "$(cat log | grep -v = | sort | uniq | tail -n 1)"

= D =

3

--

2

= 3 =

So we got the first character. I replaced the first $x with D and on to the

next character.

for x in A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 '{' '}' '!' '@' '#' '$' '%' '^' '&' '*' '(' ')' '-' '-' '_' '+' '=' '[' ']' '.' ';' '\\' '/' ',' '<' '>' '`' '~' "'" '"' '?'; do

echo "= $x ="; strace ./stage3.bin "Did_you_like_signals$x" 2>&1 | grep sigaction | wc -l

done > log; cat log | grep -B 1 "$(cat log | grep -v = | sort | uniq | tail -n 1)"

= ? =

23

So the flag is Did_you_like_signals?. I feel dirty now.

$ ./stage3.bin 'Did_you_like_signals?' 2>stage3_out.base64

Good good! Now let's play a game...

$ cat stage3_out.base64 | base64 -d > stage4.bin

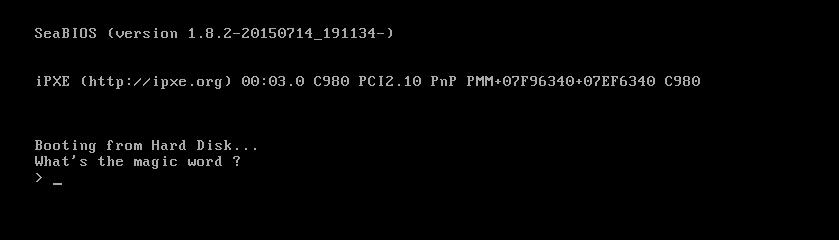

Stage 4

Unfortunately time ran out, so I didn't solve the challenge in time.

$ file stage4.bin

stage4.bin: DOS/MBR boot sector

$ qemu-system-i386 ./stage4.bin

...and we are presented with the following prompt: